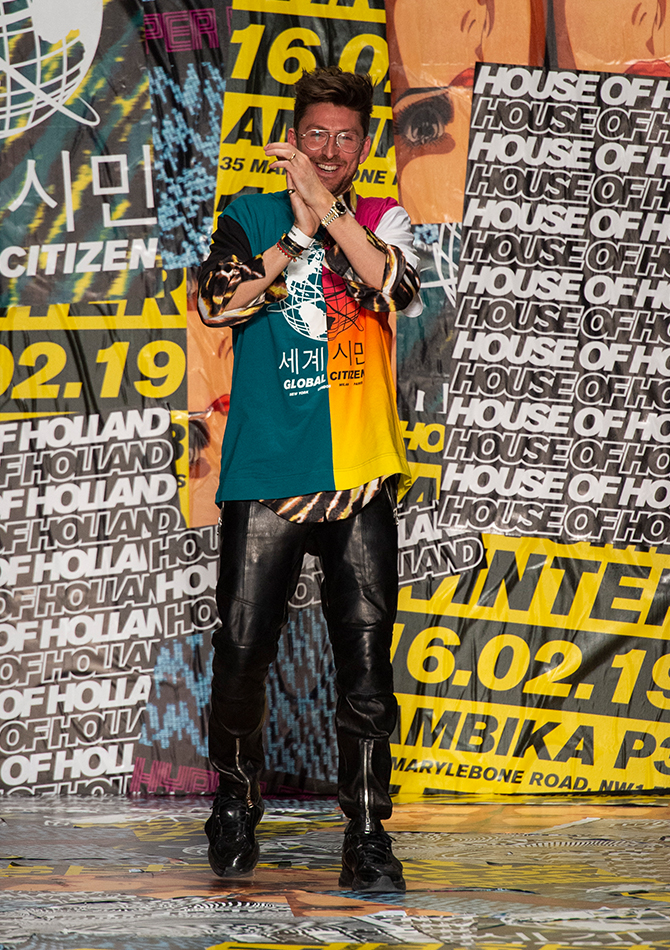

Before standing down from my label, House of Holland, earlier this year, we had staged 26 fashion shows on the London Fashion Week schedule. Over the course of this 12-year period, I bore witness to a period of seismic change in the industry. Including, but not limited to, the meteoric rise of social media, the birth of the influencer and the online retailer boom.

I staged my first show in February 2007. I had been out of my full-time job in teen magazines for less than eight weeks and invited to showcase my work as part of a group showcase for new talent (under the Fashion East banner, founded by the godmother of London design talent, Lulu Kennedy). At first, the rollercoaster of fun sustained me, until it no longer could.

There is a huge personal toll to showing your collections each season. It feels like—I can of course only speak from personal experience—that once you’re on that rollercoaster, however crazy, then to get off is career suicide. Generating, at best, snarky comments that “such and such obviously isn’t doing very well [if] they’re not showing this season.” At worst? A lack of press attention that would see global buyers, and customers alike, forgetting about your very existence.

In retrospect, HoH was probably never quite right for the concept of the fashion show. We started out as simply a T-shirt only brand and I had zero experience in pattern-cutting or creating a garment (beyond the idea of printing a witty slogan on a wholesale American Apparel T-shirt).

“A FASHION SHOW CAN COST ANYTHING FROM £30,000 RIGHT THROUGH TO OVER A £1MILLION”

As an untrained journalism graduate-cum-designer, with a strong point of view and concept of what my customer wanted, I was more often criticised for deigning the official schedule with my presence than I was celebrated with a “god loves a trier” goodwill by the critics.

“These days, people at the collections are anxiously asking each other, ‘What is the future of catwalk shows?’—but nobody seems to know the answer. House of Holland is one example, however, of what they shouldn’t be anymore,” Was one particularly painful Vogue review* that stands out. (*To be fair, that show was shit).

But, of course, I didn’t care. The draw of the attention and exhilarating joy that a twice-yearly showcase afforded my team—and my ego—far outweighed the devastating blow of a hangover spent reading a scathing review of my work. On those occasions, my competitive nature would kick in. I swiftly adopted an, “I’ll show them I deserve to be here” attitude that ultimately pushed me to work more, and try harder to produce something bigger and better the following season.

I definitely bought into the hype on occasion. I was convinced that the more press coverage I could generate, the bigger the orders from the stores would become. And for a while, it worked.

“TOO MANY PEOPLE ARE AFRAID TO ROCK THE BOAT”

There are so many elements to putting on an 8-12 minute show that many people don’t see. Finding a venue, the lighting, curating the music, seating up to 500 guests, seating plans for a VERY picky group of editors, buyers and celebrities in a way that doesn’t cause offense or upset. Casting of up to 25 girls, ensuring up to 100 pieces of clothing fit perfectly, changing from one outfit to another in under 90 seconds, inviting the right celebrities, hair and make-up, invites, filming and photography, security. It all adds up (a fashion show can cost anything from £30,000 right through to over a £1million for the big houses in Paris and New York). Within this Fashion Week hysteria, it can be easy to lose focus on the real star of the show: the collection.

Compounding this quandary is the dilemma of who the shows are for exactly. This has changed over time. Pre-internet, for example, the fashion show schedule was deigned to impress the editors, buyers and stylists who were invited. Today, the real critics are the ones who vote with their credit cards and Instagram feeds, and have the power to grow—or ‘cancel’—a brand in just one or two seasons.

The modern-day iteration of the fashion show—pre-Covid, of course—has proved peacocking to be rife. This is where the looks shown on the runway are likely made up of only a small portion of commercial pieces (that will eventually reach the shop floor), sandwiched between “show only” looks to pique the interest of stylists, editors, and influencers alike (those who have the capability to create a ‘viral’ moment for a brand). These pieces are likely to cost the most to produce, with little intention of actually producing for a customer.

And yet, the shows still go on. Why? Ultimately, it is built on an industry of personalities who love the gravitas that even attending the shows affords them (“front row only please!”). It’s a double-edged sword. This ego-stroking and adoration received for a great show drives the concept and I can’t lie… the attention feels really good. When you get it right, at least.

While Covid-19 has brought about a much needed reality check for the whole concept, it still feels like the industry is reticent to actively explore a completely new way of thinking.

Major elements of the fashion industry’s order of play come from a place of fear. Fear of no longer being the hot ticket. Fear of no longer being invited to the big events. Fear of fading into obscurity. Fear of never being able to sell a garment again. It’s this fear that hampers change. Too many people are afraid to rock the boat, to carve their own path, and set a new agenda which—however more efficient and relevant to the industry as a whole—prevents many from speaking out or actioning real change.

Even pre-pandemic, the fashion show was calling for change. With the explosion of social media almost a decade ago, it sometimes feels that the shows are no longer relevant for their current audience, and instead would make for an amazing consumer-facing event. In the same way a rock concert does for any musician.

For small brands like House of Holland, the shows were always about creating a conversation. Elevating the brand to the wider consciousness, in lieu of a year-round marketing budget. I would be the first to agree that this wasn’t always the best-serving business model for us (and if it were not for key brand partnerships for the event itself, we would never have had the budget to do so).

Looking ahead, bourgeoning labels rely so much more on direct-to-consumer business models. These real-time conversations between customers and brands have, more recently, created meaningful interactions around their cultural footprint, that had simply not happened in the past. It feels like there’s an evolving trend in the industry to look inwards, to ensure that they understand the needs of their customer. That direct feedback is invaluable.

Let’s hope the CTRL+ALT+DEL mentality that the Covid-19 pandemic has forced upon the world acts as a force for real and immediate change. That we don’t just hit reboot and hop back on the rollercoaster once more. Albeit with just 30 people in the audience.

| SHARE THE STORY | |

| Explore More |