Visual culture—be it in the form of photographs, posters or paintings—is a profoundly powerful tool in communicating ideas, sharing beliefs and representing unanimous patriotism. Regardless of our language, culture or ethnicity, the visual medium acts as a universal language that enables us to form connections and find solidarity even in the most distant stranger. Malaysia is beautiful in how it’s home to a multitude of sub-cultures and ethnicities. Although each remains distinctively unique, we are all connected through the common thread of calling this land our home.

View this post on Instagram

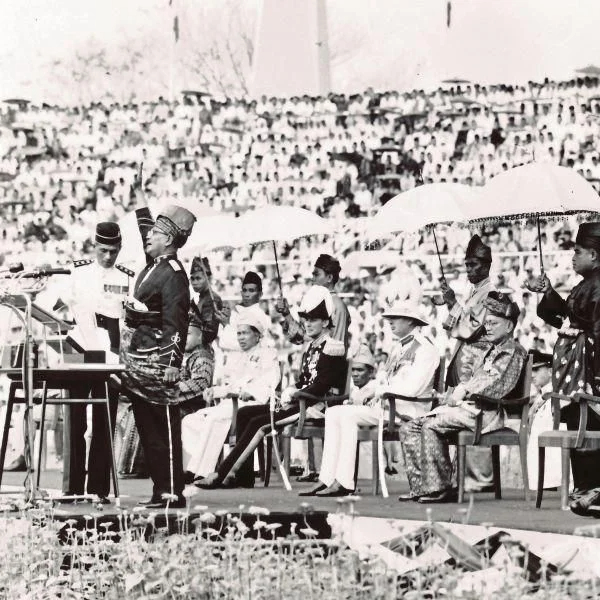

Malaysia’s historical timeline, up to this day, is marked by both triumphs and challenges—all of which have been captured visually in one form or another. One image, for example, that we are all familiar with is Tunku Abdul Rahman proudly declaring “Merdeka!” with his arm in the air. This one photograph has now grown to become an iconography of independence art; a symbol of nationalism and liberation. So much so, many of us probably don’t realise—or have forgotten—that it’s printed on our RM50 note. Although the casual nature of how we interact with such imagery may seemingly dilute the significance of it, it nonetheless presents a consistent reminder of our history and one that is cross-culturally recognised amongst all Malaysians. However, this isn’t the only instance in which the power of visual art can unite Malaysians.

In response to the ongoing pandemic, the #BenderaPutih movement emerged. A white flag is the simplest and most raw of images, yet it had an incredibly powerful and touching ability to connect Malaysians in times of need. This one symbol has highlighted the extraordinary sense of community that this country embodies.

Likewise, seeing the national flag—the ‘Jalur Gemilang‘—in the month of August ignites a degree of patriotism. The dynamic and ever-changing fluidity of political, social and cultural climates has brought about various different visual icons; these have all, in one way or another, created a distinctive Malaysian collective. In a multi-cultural society such as ours, visual language needs no translation: We merely contextualise a pivotal moment through its place in Malaysia’s historical timeline.

View this post on Instagram

Although the history of our land is said to date back to 1400 AD, we’ve decided to only cover key moments from 1941 onwards. Due to the complexities and polarising ideas that surround each moment (both locally and internationally), the brief descriptions are merely to communicate and accompany the images that (alongside many more) are now emblematic of Malaysian history.

1941-1945: The Japanese Occupation

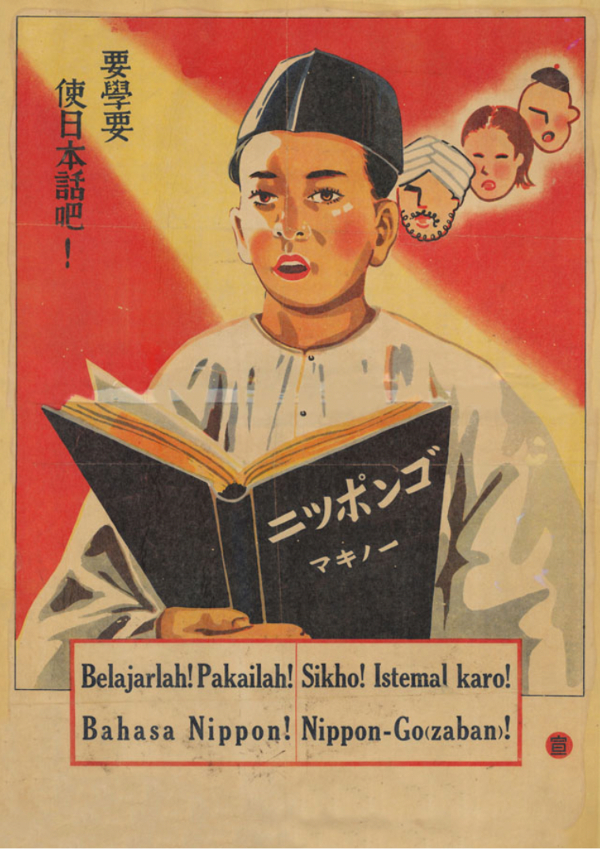

Japanese soldiers invaded Malaysia in 1941 after the Pearl Habour attacks in America. Taking local residents largely by surprise and force, they soon gained control of the entire peninsula (including Singapore).

In ‘The Ambivalence of the Reaction, Response, Legacy and War Memory’ by Peter Alan Horton, the Japanese used propaganda posters and slogans to promote the discourse of ‘Asia untuk orang Asia’ (Asia for Asians). Many posters emerged to spread the idea of Japanese saviour-ship from Western colonisation, creating the illusion of allyship to win the support of Malaysians. These glossed over the grotesque ethnic divide and brutality endured by many Malaysians at the hands of the Japanese military.

1945-57: The British re-occupy Malaysia and anti-colonial movements take flight

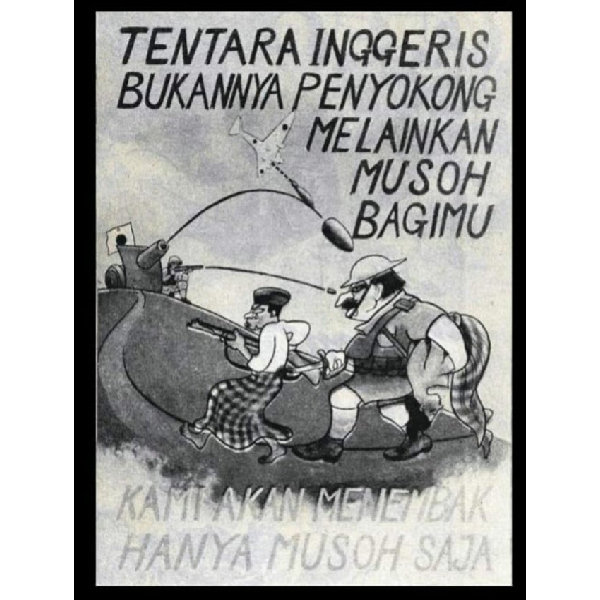

Although it’s documented that most locals welcomed the defeat of the Japanese in 1945, the British seizing control soon after was met with great disdain. Research shows that in Malaya, WWII was the catalyst for anti-colonial movements. Thus, when the British came back into power and realised they were not welcomed, they strategically adopted a tough stance.

Part of these strategies involved acerbating the ethnic divide that emerged during Japanese rule. By utilising negative propaganda to delegitimise nationalist movements, they portrayed these efforts as dangerous acts of rebellion. The British also attempted to manipulate public opinion by promoting the idea that they saved Malaysians from the Japanese and, thus, were “allies”.

1948-1960: State of emergency with communist insurgency

The chaos ensuing from Southeast Asia’s cold war, along with the end of Japanese occupation, enabled communist ideology to take root and grow. The British considered the communists a large threat to their government.

A guerrilla war emerged from this conflict, fought by communist pro-independence fighters of the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) and the Malayan Communist Party’s (MCP) armed wing, against the armed forces of the British occupation. The British took this opportunity to link the anti-colonial movement, especially in 1948, to the communist threat. A state of emergency was declared. Although the MNLA and MCP differed in political views and desires, they mutually opposed British colonialism. Many posters emerged, from both sides of the movement, to win over citizens.

View this post on Instagram

| SHARE THE STORY | |

| Explore More |